| DMH Spotlight - Who was Istvan Bibo? Could he have sketched Carl Henry in Paris? | Back |

http://hungarianspectrum.wordpress.com/2011/08/15/istvan-bibo-august-7-1911-may-10-1979/

István Bibó (August 7, 1911- May 10, 1979)

August 15, 2011

István Bibó is considered by some to be the greatest Hungarian political thinker of the twentieth century. His published writings appeared primarily between 1945 and 1947, the period he deemed the most important in his whole life. He suggested that the epitaph "István Bibó, lived between 1945 and 1947" be inscribed on his tombstone.

He was rediscovered after his death when members of the democratic opposition decided to publish a memorial volume of essays in his honor. Considering that István Bibó for a few days was a member of Imre Nagy's second government in 1956 and after the revolution he was sentenced to life imprisonment, the authorities refused to grant permission to have the volume published which eventually appeared in samizdat. According to some analysts it was István Bibó who managed to bring together the two warring factions of János Kádár's opposition: the urbanites and the "narodniks." Today we would call these urbanites liberals; the narodniks by now can be safely placed right of center. Sometimes even way right of center. But, as Krisztián Ungváry remarks in an essay written for the occasion of the Bibó centennial, out of the ten editors of the volume there was only one person from the "völkisch" side, Sándor Csoóri. Jen? Szücs, the medieval historian, couldn't be placed in either group. The rest were former urbanites/liberals.

Bibó is greatly revered in liberal circles. Although Viktor Orbán and Fidesz occasionally pay lip service to Bibó's work and significance, he could not possibly speak the language of today's Fidesz. That despite the fact that early Fidesz history is organically connected to a dormitory/specialty college that was later named after István Bibó and where several of the founders of the party lived while in university.

However, says Ungváry, Bibó was not a liberal, and he brings up a few examples to prove his point. I must say that these facts of Bibó's life were unknown to me. For example, he didn't think that the introduction of universal suffrage or the full-fledged functioning of a parliamentary system would be appropriate until "political and moral regeneration" takes place. He also considered the mass migration of former Arrow Cross members into the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) inevitable.

There is no question about Bibó's moral stance, which was indeed exemplary, but some of his political value judgments are questionable. As an internet friend remarked years ago: "István Bibó was an excellent man who joined the wrong party." He opted for the Peasant Party which, as it turned out, was the creation of MKP. I'm sure that Bibó was not aware of the fact that some of the leaders, like his old friend from school days, Ferenc Erdei, were secretly also members of the Hungarian Communist Party.

There are a few works of Bibó that every educated Hungarian must read. For example, "Zsidókérdés Magyarországon" (The Jewish Question in Hungary). But when it came to practical politics of the immediate post-1945 years Bibó could exhibit extraordinary naiveté. I remember when I first picked up Bibó's essay on "The Crisis of Hungarian Democracy," I stopped dead at the very first sentences: "Hungarian democracy is in crisis. It is in crisis because it lives in fear. It has two kinds of fear: it is afraid of the proletarian dictatorship and it is afraid of reaction. There are no objectively grounded reasons for either fear. Those in Hungary who want to establish a proletarian dictatorship and those who want the return of the old regime are in a significant minority. Moreover, outside forces would not welcome either turn of events." How wrong Bibó was or how naive. Of course, there was plenty of reason to fear that the Hungarian Communist Party with the Red Army in place was building a road toward proletarian dictatorship during 1945 and 1946.

Bibó later in life acknowledged his own naiveté. Although in his last years he wrote almost nothing, he gave a long interview before his death in which he said that "I know that my complete work is hopelessly naive, as my writings during 1945-46 were naive." Ungváry considers Bibó's blindness toward the machinations of Mátyás Rákosi's communists more than naiveté. Here, in my opinion, Ungváry takes an intellectually dangerous turn, trying to psychoanalyze Bibó.

Bibó was implacably harsh against himself, against his faults. And because he considered himself a member of the Hungarian Christian middle class whom he found for the most part guilty of political and moral blindness that led the country to the precipice, he overcompensated, says Ungváry. For example, after the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty, Bibó uttered a sentence Ungváry finds horrible: "Hungary got what it deserved." To his mind, the treaty was punishment for the wrongs of the Christian-national regime.

As for the Jewish question, Ungváry claims that Bibó didn't always see clearly on the question of Hungarian-Jewish relations. For example, he refused to sign the petition of the intellectuals against the so-called Jewish laws of 1939 because the petition said nothing about the deprivations of the rights of Hungarians. Perhaps, continues Ungváry, Bibó's reaction after the Holocaust is more understandable. He felt shame as a result of the Christian national middle class's behavior after the German occupation and during the Szálasi period. One also has to bear in mind that his closest friend, Béla Reitzer, died in 1943 somewhere in the Ukraine as a member of a Jewish labor battalion.

In addition, there might have been other psychological factors that led Bibó in a direction closer to the left. His father-in-law, Hungarian Reformed Bishop László Ravasz, as a member of the Upper House spoke in favor of the second Jewish Laws. Although Bibó never talked about it, Dénes Bibó, his uncle, was a favorite of Pál Prónay, the notorious white terrorist, responsible for the deaths of perhaps hundreds of Jews and non-Jews. Dénes Bibó is described in the index of names of A határban a Halál kaszál: Fejezetek Prónay Pál naplójából as "a most cruel terrorist." (An interesting footnote to family history. István's Bibó's paternal grandmother was of Jewish origin. I wonder what Prónay would have thought, if he knew that his favorite officer was half Jewish!)......

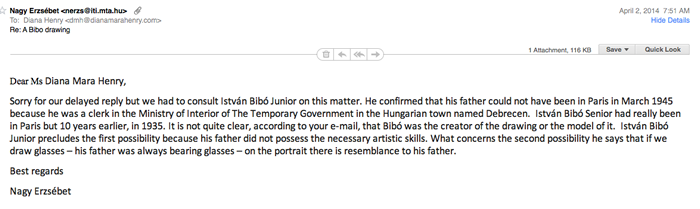

Detailed information can be acquired about the activity of the Center at www.bibomuhely.hu. The secretary of the Center, Ms Erzsébet Nagy can be contacted for the most recent information at nerzs@t-online.hu or nerzs@iti.mta.hu. The international account number of the foundation of the Center is: HU71-10102086-46991000-01000000.

Budapest, December 1, 2005

Gábor Kovács - László Perecz