| DMH Spotlight - Boris Pahor born 28 August 1913 | Back |

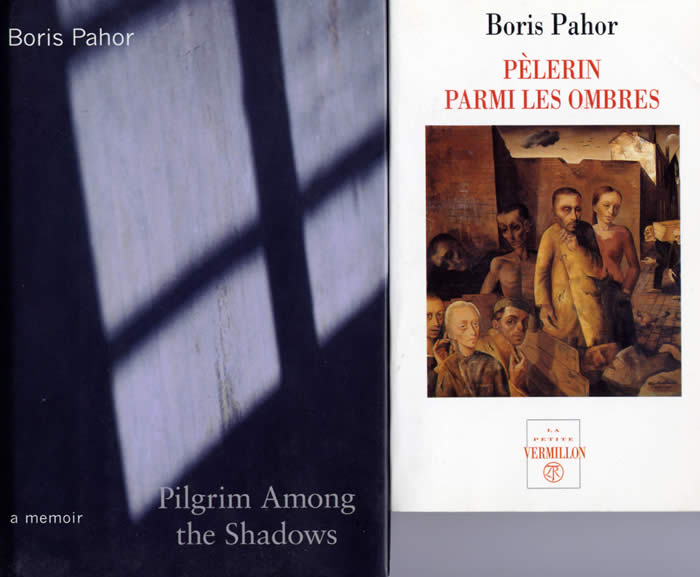

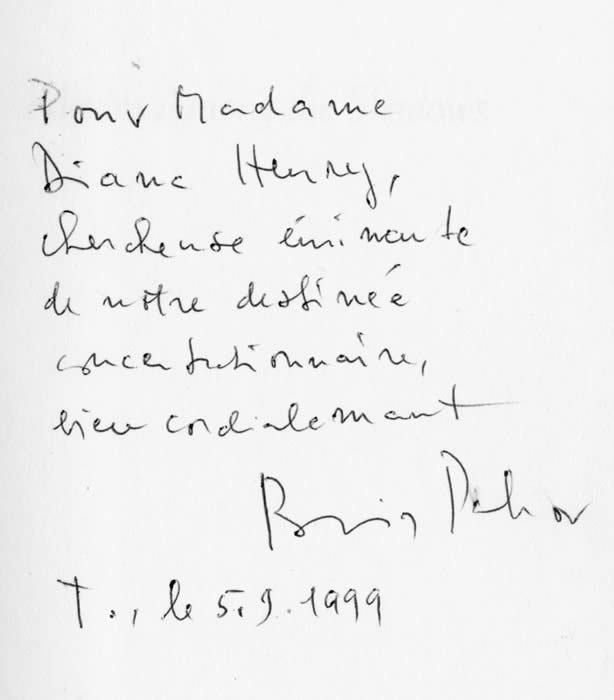

The author Boris Pahor, a Slovene of Trieste, is famous in Europe although less well known in the US, his only novel translated into English being Pilgrim Among the Shadows, an astounding memoir of Natzweiler (Harcourt, Brace, 1995.) As I have corresponded with him extensively about his Natzweiler experiences, and also have a copy of a video about his return to Natzweiler, he has been so very kind to send copies of his books, including one with the inscription, below: For Mrs. Diana Henry, eminent researcher of our concentration camp destiny, Very cordially, Boris Pahor, T(rieste), September 5, 1999.

Write to us to get copies of 3 important letters to DMH from Pahor describing his work

and those he knew at Natzweiler.

The following is a translation of Postcript by Thomas Poiss to the German language edition of Pahor's memoir of Natzweiler-Struthof, Nekropolis, as translated by Thomas Marc Futter for this site:

The mischief started, as so often in the 20th century: somebody must have slandered Boris Pahor when, in January, 1944, in Trieste, German secret police came to fetch him, subjected him to the usual brutal examination, and within a short while, deported him to Dachau. The truth is that Pahor had not yet had time to become involved in the Resistance, since he had just --- following Italian war service in Libya and as prison translator at Lake Garda --- returned to his home in Trieste where the Slovenian liberation front OF had been in operation with some success. The trap door closed in spite of this. Two newspaper articles in the Nachtkastchen

(Nightbox) were enough to send Boris Pahor for fifteen months into the German Death Reich: Dachau, Natzweiler in the Vosges mountains, Dora- Mittelbau, and Hartzungen/Bergen Belsen.

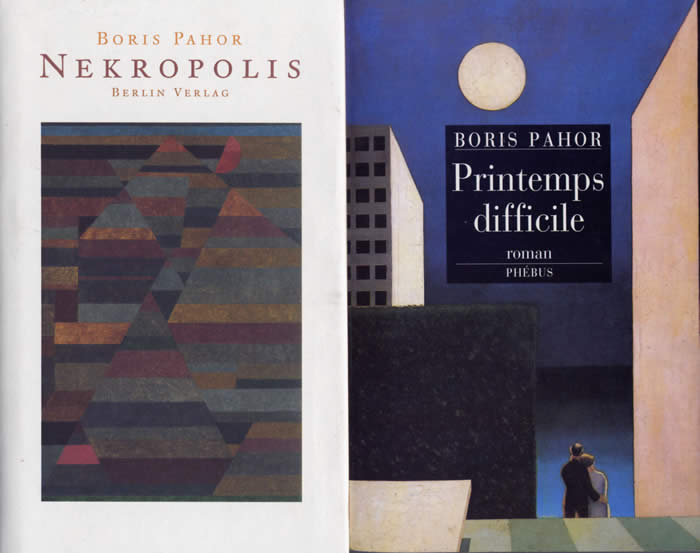

Boris Pahor relates his way through Nekropolis --- the name relates to the description of the French memorial at Natzweiler: nécropole national ---

but he doesn’t tell anything in chronological or thematic order, but in a manner that protects us later-born, at the same time in a more emphatic way. The experiences are related from the perspective of a summer’s day in the early Sixties, when the author is strolling along the memorial site of Natzweiler. He is walking in eye- and earshot of the official leading a group through the camp and follows the impulses of the spontaneous memory from which he can obtain a very intense picture of the organization of the camp, exactly because the most powerful pictures gather around the remembered details. At the same time, Pahor is reflecting in his lonely walk across the terraces of the camp --- down below, the crematorium, up above, the gallows, and in between, the tiered barracks, connected by staircases --- the possibility and impossibility of making any kind of statement. His own light summer shoes are reflected in the gravel but seem completely unreal vis à vis the remembrance of the plump, often unusable wooden clogs in which he at times used to be chased or which he was wearing whenever the dead were carried from the sick barracks to the oven. When, however, his own present time resists past memories --- how should a former prisoner explain himself to anyone who was not affected by the events themselves --- vacationing tourists when their imagination becomes overloaded by the simplest happenings? “What is that? - The oven. The poor ___” and at the same time the story teller who has to listen to this banal dialogue knows that it is only the usual excuse of a weak consciousness in the face of the suspected reality.

In constantly new attempts, Pahor circles around the question of communication while time and time again being pulled into ascending remembrances: into the rain, into the cold, into the pointless harassment or the sadistic guards, the illnesses. In the regard to the last named, we discover, particularly intensively, because Pahor, who had no political direction nor had been a member of the hierarchy of the prisoners, only got to know the camp through his multilingualism and his ability to care for the sick. In changing bandages, a French camp doctor noticed the many languages of the man with a capital I that stamped him as an Italian, who through his Slovenian, also knew the Slavic languages and in addition knew the German that was a requirement for the official sick reports. So Pahor became one of those who fought with paper bandages, grape sugar, animal carbon and in the best case, with veterinary medical sulfanimides against diarrhea, inflammation/ infection, open sores of hunger, edema, and similar severe suffering. Too many times the activity of those caring for the sick was transformed into that of gravedigger. In consideration of this, it would appear to be a miracle that Boris Pahor escaped with only pulmonary TB. Of these medical therapies in a French pulmonary sanitorium, and of the difficult return into everyday living, he relates in an autobiographical novel, Kampf mit im Frühling.(1958, dated 1997.)

Boris Pahor approached the theme of Nekropolis very slowly. In Kampf mit im Frühling, he relates --- embedded in the equally strange but healing love story --- the experiences in a concentration camp in two chapters, while in a preceding novel, La Villa sur le Lac (1998) this is only present in an indirect way. The protagonist an architect from Trieste who is on vacation in Lake Garda, discovers the emotional and still standing relics of Mussolini’s time, but is reluctant to tell his young beloved about his own experiences. But in the Sixties, the time is ripe to take the related beginnings of the immediate postwar years --- the episode of the caretaker Yanos (Nekropolis page 98 and following) was already told as a separate story in 1947 --- to put them together into a many faceted representation.

The storyteller of Nekropolis mostly knits together several perspectives and often achieves his disturbing clarity through careful guidance of the reader. For example, Pahor walking through the barracks of Natzweiler hits upon the wooden horse to which the victim of whippings were tied. But he is not focusing his view onto this terrible event which cannot be reached through any amount of pity but because of the absence of the banished prisoners from the call up (appel.) They are only waiting that the presumed victim who may have walked away and is sitting in another corner and fallen asleep from exhaustion that the guards will find them. Only in realizing this silence they will follow the expected identification with victim, but even this does not happen until the panicky moment of discovery at the moment of extreme isolation.

Printemps difficile is a starkly beautiful love story of partial recovery and complex return to society in the immediate era of post-war Paris and the sanatorium. Probably a near-universal story of a veteran's return.

Another excellent autobiographical novel: after-return to the hotel in Italy where the freedom-fighter was turned over to the Fascists.